The North Face of Dragontail: lean and cold

Dark air interuppted by sparks of light, my picks find no resting place. I hook an edge, match a tool, and throw the other in five-inches of snow on rock. Shifting my body weight onto the slab, unexplainable forces bond water and stone. I don't fall. As I go higher the snow is deeper and more secure, but I know it will only last until the next rock band. All too soon I am forty feet out again, trusting life and limb to a frozen disc of moss, feet splayed out on steep verglased blocks of granite. I don't want this challenge turned nightmare to last any longer.

Cole following low on the route

"Oohh!" Cole's monkey call pushes through the winter forest. I step akwardly over a fallen log and gaze at the north face of Dragontail. Even though I've summited many routes on this peak I feel intimidated. 2000 feet of rock and snow on a mile wide face has me feeling small, so I turn my focus to the trail in front of me. One foot in front of the other and we're setting up basecamp in a shifting fog. The sun falls, but light is constant in a rising full moon. I hold hot choclate between sweaty palms and let my eyes follow a cold path up skinny couliors and tilted snowfields. The cruxy rock bands that seperate easier ground look difficult, but passable. That night, Cole and I stare at the illuminated cieling of our tent, each lost in excited thoughts about the day to come. "Remember when we used to bike and bus to Little Si (the local crag we learned on)? I could never sleep before those days either," I reminicsed. "Tell me about it! I haven't slept in three nights!", said Cole. Between packing, approaching, and finally climbing, there had been plenty of excitement. Finally, I hear Cole snoring. I follow his lead into my own dream world just as the full moon slips beyond a ridge and darkness settles in.

The slow return of light and a new day evolves seamlessly from the night. A heavy fog obscures the rising sun as our Dragonfly roars through the gloom. Soon we crampon towards the Gerber-Sink and start up. We are prepared for a neve dash to the summit, armed with a few pieces. We use a 40 meter rope, hoping to move together up the face in a matter of hours. The difficulty of the first two rock bands suprise me. I'm using every trick in the book and fighting hard for pro. I think of retreat, but then a fun coulior and a snow field push me a few hundred more feet towards the next rock cliff. As always, Cole follows quickly and efficiently with no complaints about the long belays and difficult climbing. I make one more horrific lead to a hanging snow field that looks to promise quicker movement for the remainder of the route. Unfortunetely, challenging conditions have forced me to climb variations that are less direct and as darkness falls we hang from an off-route snag cemented by snow and stone and eat a bar for the first time all day. The climbing has been some of the scariest I have ever experianced. Every pitch I dig through snow to find a few pieces that are barely adequete. Most of the time those pieces are well below my boots while I execute hail-mary mixed moves. This brings up an important question. Why am I doing this?

I don't know.

But I do know we are not going down anymore. I look over my left shoulder and follow our boot tracks down the face until they blend into black granite. Our rope wouldn't even make that rappel, I think. I start off into the night shift, frustrated at our predicament, but committed to climbing as quickly as I can to the safety of the summit coulior. I arc leftwards for a few hundred feet, before moving up into the final difficult stretch of climbing. I begin to lead, but return to the belay, cursing the unprotected, scratchy mixed ground I am on. My brain is mush. "These leads are killing me Cole," I whimper. For a moment I feel the end of my ropes slipping through my palms. I arrest the lack of confidence, shove it deeply away, and find a place next to Cole to rest for a bit. Another bar and ten minutes of shut eye are all I get before I am out on the lead again. The final step holds a few inches of sugar snow over rock. I pendulem between different snow patches, trying to gain elevation any way possible. Finally, I am 40 feet from the end of the pitch. All I have to do is go for it. A thin snow finger wiggles upwards before me. I know there will be no pro, but I pray for a stick or two at the final bulge. Charging upwards I don't think of falling this time. Frozen moss and a kamikaze scream of adrenaline propel me through the pitch and into the coulior above. "600 easy feet to the summit," I think as the sun rises. Of course it is beautiful and Cole and I gawk at the views of our beloved Cascades. For a few minutes we forget the horrors of the past hours. Perfect, moderate snow climbing in an intense alpine setting takes us to the top. We high five and laugh.

Myself in the final coulior

Summit shot

Our descent is quiet. We both think about life, climbing, and our choice to push the envelope like we do. By the time we are back at base camp I am seeing visions. I am so worked. We fire up the stove and begin hydration and nutrition exercises. We need food and water badly. Cole tries to remove his boots, but finds the toe area of his right sock to be a solid block of ice. Only 30 minutes of thawing over the stove allows him to remove the sock and get his boot back on. His feet look wet, but normal and soon we are hiking the ten miles towards our car.

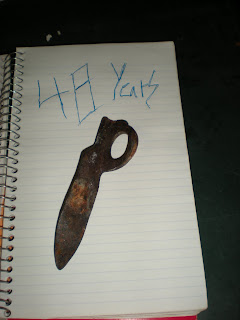

"What's up homie." Cole is still in bed. He sits up. "Are you going to work today?", he asks. Even though the last 48 hours stretched us beyond our limits, I have things to do and plan to resume normal life this very morning. "I think I bruised my toes in those boots. They are so damn small." I look at Coles feet and my heart sinks. Even though I've never seen frost bite in person, I can recognize a cold injury. After some research and a few phone calls I am feeling scared. His feet are clearly in serious condition. We end up in the ER and learn that he in fact does have a fairly severe case of frost bite on six toes. I stare at the steril white walls and curse myself over and over. Why didn't I bail when I knew the climbing was taking too long? Why wasn't I more concerned about cold injury, especially knowing that Cole's foot wear was questionable? Why, why, why...the wheels spun out in my brain.

Reality check

So, that brings me to today. Cole is recovering on the couch after a week of questions and finally anwers. It looks like he will be keeping all of his digits, which of course was a our major concern, but his road to recovery will last months. It hurts to see my friend in pain. Damn the mountains. But even now, I am dreaming of another winter battle. Climbing, no matter what, will always inspire me to push my limits for reasons known and unknown, but the past week has been grounding. I feel like I let my perspective slip up there on Dragontail. Our experiance wasn't worth Cole's pain. I should have bailed when I knew how difficult and cold the climbing was. It's hard not to fall into the hype of hard sends and high summits, but the reality is mountains are uncaring and kill with no mercy. 2009 has made that clear to the climbing community. Everyong knows the saying, "What doesn't kill you makes you stronger." I certainly hope that applies here.